While I’m loath to admit it, even in the face of adroit hustings maneuvering, the Conservative party is running a near flawless campaign. And yet, I must vouch my Liberal allegiances before they are metaphysically revoked. So here goes. Stephen Harper will never earn my trust (his eyes, particularly in those egregious excuses for political ads the Conservatives are running, betray an evil of the worst kind; or there’re just tragically misshapen – ed.) however, the Conservatives have been nothing less than spectacular. OK, I’m being a tad facetious. But altogether, they have been ably up to the task of deliver the goods day in and day out, offering fresh idea after fresh idea.

Apropos, yesterday’s announcement of a $500 tax-credit for families with children under 16 involved in sport and physical activity was just another example of their growing appeal. And to name it a Sports credit? Pure genius! Along with the proposed GST percentage point cut and the income tax shelter for seniors, among others, the Conservatives have not only charmed the message much like a snake charmer but have also managed to stroke some psychological sweetspots that can’t but arouse interest among even the most liberal.

There have, no doubt, been a few hiccups, like Brian Pallister infelicitous gaffe regarding women and their inability to firmly answer questions. When asked to clarify his comments, which weren’t taken out of context primarily because they were delivered in front of a camera to an interviewer, he gave the predictably pat and therefore predictably flimsy response that is characteristically know as a mea culpa – he said he was taken out of context. But the story, your run-of-the-mill ‘Conservatives are out of touch with the mainstream of Canadian social values’, a story so quickly amplified by our ‘Liberal media’s’ journalistic aplomb, had no legs.

The Conservatives, it would appear, are getting a fairer shake this time around, if only because the country is in the throes of an insurgency of lethargy. People are simply tired of hearing anything the Liberals have to say. Anything! It’s the curse of being electorally successful for too long, the point at which returns begin to diminish. Aside from Paul Martin’s intention to ban handguns, which would be momentous if it weren’t so after-the-fact, the Liberal campaign has been a woefully tedious mess.

Communications Director Scott Reid’s fine contempt toward what families would spend their childcare dollars on under a Conservative plan -- beer and popcorn, as he sees it -- was met with the necessary opprobrium from all sides. And for all their public relations acumen, to counter Mr. Reid wry remarks the Liberal's took a descent into gay marriage demagoguery; a tired and unqualifiedly uninspired tactic. It was so incongruous to hear Mr. Martin fulminate about the threat the Conservatives posed to gay marriage. It was so 2000! Isn’t same-sex marriage already the law of the land?

Recent polls have been fairly static, The Liberals still manage to hold a seven to eight point lead over the Conservatives nationally, and in Ontario the Liberals are polling relatively well. But the trends seem to show a gradual warming towards the Conservative message in general, which has meant a virtual bottoming out of NDP support in Ontario. NDP support usually shifts to the Liberals strategically in an attempt to hedge Conservative gains. So now the question can’t help but reveal itself: Wither the Liberals?

* * *

A banishment to the political wilderness may be exactly what liberalism in Canada needs, in my opinion. I’m all for some type of political time-out to allow the Liberals to get their shit together. Or just get a breather at least. As a result of the dearth of ideas, an utter lack of principle, of direction, and, more prominently, of leadership, a programmatic and intellectual refashioning of liberal ideas is badly needed. And though I may be contradicting what I wrote in my last post, which was intended as pure political strategy, Stephen Harper is no more a leader than Paul Martin is. Paul Martin is a leader only because of his experience -- and by default.

A Conservative minority government wouldn’t necessarily be a horrible thing. The de facto Prime Minister Harper would be de jure powerless. In this scenario, the balance of seats in the house would be held by a generally centrist and social democratic rabble of MP’s. The Liberals will have an opportunity to go sit in the corner and think about of what they’ve done to the county.

Tuesday, December 13, 2005

Monday, December 05, 2005

Message

The Canadian federal election is fully underway with hardly a step being missed by each political party, both in tone and message. Out of the gates first are the Conservatives, whose consistency and discipline has enabled them to frame the debate thus far.

Stephen Harper and his outfit have done an excellent job getting out message faster than the Liberals. For example, the proposed GST cut is undoubtedly a policy chestnut the Conservatives have been holding on to a for while now, and in the midst of the holiday shopping season functions more as a psychological boost than sound economic policy.

Jack Layton has stuck to the tried and true NDP hobbyhorses, health care, the environment, and education. But his electoral fortunes look to be much worse than if he continued to prop-up the minority Liberal government. Mr. Layton is no longer the most powerful man in Canada.

In the sponsorship scandal’s fallout, Gilles Duceppe and the Bloc are polling strong in Quebec, and no less a character than André Boisclair, the PQ's newly elected leader, makes the prospect of Separatist resurgence very real.

Paul Martin’s Liberals are doing what sitting governments mired in corruption allegations do, staying out of the headlines.

And it’s not exactly hurting them either. In a CPAC-SES poll conducted last night (Random Telephone Survey of1200 Canadians, MoE ± 2.9%, 19 times out of 20) the Liberals have 38% of decided voters’ support, a pick up of 4%, while the Conservatives have 29% of decided voters’ support, a drop off of 1%. This even despite last week’s strong campaigning by the Conservatives. Even more troubling for the Conservatives is the strong polling for Unsure, 20%, for Best PM, surpassing Stephen Harper’s 19%. And when it comes to trust, competence and vision on a Leadership index, it’s not even close: Martin is 30 points ahead of Harper, who seems to be losing ground.

This brings me to what Iwanted to say -- prefaced and couched as it is with the skeletal of bare journalistic requirements. Earlier this morning, Paul Martin gave what I think was a terse and piquant speech that should crystallize the Liberal message for the remainder of this election. His essential point was that leadership matters, or leaders matter – which ever way has more purchase. For all his otherwise charming deficits, Paul Martin projects the characteristics most closely associated with leadership better than Stephen Harper. One simple metric could be who wants the job more. Stephen Harper has always been a reluctant leader, quick to cut himself from party doyens. Paul Martin, on the other hand, has wanted this job since lord knows when. Another metric is international visibility, which Martin wins hands down – this isn’t a fair match for Harper.

So if the Liberals want to do well, I believe, they have to change the scope of their message. Healthcare is a dead metaphor, literally. There is a fatigue and growing malaise anytime the subject to brought up. It’s neither comprehensible as a general election question -- it’s too over wrought -- or palatable for reasonable dialogue. It is the stuff of antiseptic bromides and ridiculous tautologies. (“Fix HealthCare for a Generation”) Leaders, in light of our particular historical situation, matter. When international tumult threatens to damage the already threadbare international order [fill in obligatory analogy] who we elect reflects what we believe. Our Prime Minster must not only lead Canada, but represent Canada to the world. Now here there are obvious undertones of Bush and America’s perception throughout the world. (This tact must be navigated adroitly and great expense must be taken not to directly critique Bush – oblique criticism is permitted) Martin and the Liberals win this way. Liberal Message needs to raise the altitude coming into January.

I felt very strongly about getting this idea to the Liberal party, so much so that I called the PMO (Prime Minister’s Office) which is a listed number on the Government of Canada’s website, and asked to speak to David Herle, a Liberal campaign strategist. To my amazement I was put through, or at least I assumed I was. His assistant informed me that he was on the other call and would get back to me when he was free. I was slack-jawed, although still very skeptical. Not to appear of bad repute, even though in their eyes I most certainly am, I left my real name and real number.

It turns out that my call may have been transferred to the PCO (Privy Council Office) which ‘provides public service support to the Prime Minister’, and security no doubt. Why do I think this? Well, it turns out that a recent visitor to my site works at the Privy Council Office and was likely checking the nature and content of my blog; this hardly bothers me – I welcome all eyes.

They justifiably assumed that something was amiss. A man calling the PMO and asking for a Liberal strategist? As if that’s possible. That I could call and be transferred to the Liberal War should be a testament to the accessibility of our country’s political machinery. But that’s too much to ask, and a service no political party should even entertain. Yet, there is something to be said about taking to pulse of the common man. To the PMO and PCO, no harm was intended. To David Herle, give me a call sometime, I have some good ideas.

Stephen Harper and his outfit have done an excellent job getting out message faster than the Liberals. For example, the proposed GST cut is undoubtedly a policy chestnut the Conservatives have been holding on to a for while now, and in the midst of the holiday shopping season functions more as a psychological boost than sound economic policy.

Jack Layton has stuck to the tried and true NDP hobbyhorses, health care, the environment, and education. But his electoral fortunes look to be much worse than if he continued to prop-up the minority Liberal government. Mr. Layton is no longer the most powerful man in Canada.

In the sponsorship scandal’s fallout, Gilles Duceppe and the Bloc are polling strong in Quebec, and no less a character than André Boisclair, the PQ's newly elected leader, makes the prospect of Separatist resurgence very real.

Paul Martin’s Liberals are doing what sitting governments mired in corruption allegations do, staying out of the headlines.

And it’s not exactly hurting them either. In a CPAC-SES poll conducted last night (Random Telephone Survey of1200 Canadians, MoE ± 2.9%, 19 times out of 20) the Liberals have 38% of decided voters’ support, a pick up of 4%, while the Conservatives have 29% of decided voters’ support, a drop off of 1%. This even despite last week’s strong campaigning by the Conservatives. Even more troubling for the Conservatives is the strong polling for Unsure, 20%, for Best PM, surpassing Stephen Harper’s 19%. And when it comes to trust, competence and vision on a Leadership index, it’s not even close: Martin is 30 points ahead of Harper, who seems to be losing ground.

This brings me to what Iwanted to say -- prefaced and couched as it is with the skeletal of bare journalistic requirements. Earlier this morning, Paul Martin gave what I think was a terse and piquant speech that should crystallize the Liberal message for the remainder of this election. His essential point was that leadership matters, or leaders matter – which ever way has more purchase. For all his otherwise charming deficits, Paul Martin projects the characteristics most closely associated with leadership better than Stephen Harper. One simple metric could be who wants the job more. Stephen Harper has always been a reluctant leader, quick to cut himself from party doyens. Paul Martin, on the other hand, has wanted this job since lord knows when. Another metric is international visibility, which Martin wins hands down – this isn’t a fair match for Harper.

So if the Liberals want to do well, I believe, they have to change the scope of their message. Healthcare is a dead metaphor, literally. There is a fatigue and growing malaise anytime the subject to brought up. It’s neither comprehensible as a general election question -- it’s too over wrought -- or palatable for reasonable dialogue. It is the stuff of antiseptic bromides and ridiculous tautologies. (“Fix HealthCare for a Generation”) Leaders, in light of our particular historical situation, matter. When international tumult threatens to damage the already threadbare international order [fill in obligatory analogy] who we elect reflects what we believe. Our Prime Minster must not only lead Canada, but represent Canada to the world. Now here there are obvious undertones of Bush and America’s perception throughout the world. (This tact must be navigated adroitly and great expense must be taken not to directly critique Bush – oblique criticism is permitted) Martin and the Liberals win this way. Liberal Message needs to raise the altitude coming into January.

I felt very strongly about getting this idea to the Liberal party, so much so that I called the PMO (Prime Minister’s Office) which is a listed number on the Government of Canada’s website, and asked to speak to David Herle, a Liberal campaign strategist. To my amazement I was put through, or at least I assumed I was. His assistant informed me that he was on the other call and would get back to me when he was free. I was slack-jawed, although still very skeptical. Not to appear of bad repute, even though in their eyes I most certainly am, I left my real name and real number.

It turns out that my call may have been transferred to the PCO (Privy Council Office) which ‘provides public service support to the Prime Minister’, and security no doubt. Why do I think this? Well, it turns out that a recent visitor to my site works at the Privy Council Office and was likely checking the nature and content of my blog; this hardly bothers me – I welcome all eyes.

They justifiably assumed that something was amiss. A man calling the PMO and asking for a Liberal strategist? As if that’s possible. That I could call and be transferred to the Liberal War should be a testament to the accessibility of our country’s political machinery. But that’s too much to ask, and a service no political party should even entertain. Yet, there is something to be said about taking to pulse of the common man. To the PMO and PCO, no harm was intended. To David Herle, give me a call sometime, I have some good ideas.

Thursday, November 03, 2005

Indecision

Dwight Wilmerding is an erstwhile employee of the Pfizer Corporation, having been fired from an ambiguously unsatisfying technical-support job that, come to think of it, was probably going to be outsourced anyhow. Listless, unmoored, and an altogether likeable lay-about, Dwight is the feckless 28-year-old protagonist in Benjamin Kunkel’s first novel Indecision. Kunkel, 32, is one of the founding editors of n+1, a ‘little magazine’ in the mold of a Partisan Review circa. 1940’: a cadre of aspiring New York Intellectuals serious about literature and political and cultural criticism. It should go without saying, then, that Indecision should be a fictional vehicle to push his thus far imbibed political idiosyncrasies, and on a crass level it is. But Indecision turns out to be more+1, philosophic and cleverly comic at length, though evocative and poignant when the narrative permitted.

Our aforementioned hapless narrator suffers from abulia, “Loss or impairment of the ability to make decisions or act independently”, a fittingly postmodern condition which, fittingly enough, has a postmodern biomedical cure, namely the drug Abulinix. So racked with indecision Dwight is that he’s resorted to flipping a coin to determine his actions – yet somehow still ends up feeling ambivalent. The root of this irresolution, it can be gleaned, is Dwight’s overall sense that, with the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, liberal capitalism seems ineluctably directionless, with no end in sight, or impedance in path, and certainly no morality at its core. All this seems to imply that his particular life is without consequence.

Wryly glomming over what his maybe-possibly-girlfriend Vaneetha has just said, Dwight has resigned himself to being just another cliché:

When one of Dwight’s roommates, a putative medical student, offers him Abulinix for his indecision, Dwight contains his enthusiasm, since an otherwise decisive yes would disqualify him. But it’s a clinical trial and likely side-effects are bound to be prohibitive to his taking the drug, right? No. Dwight dives in headlong hoping, in the process, to figure out his ‘romantico-sexual’ situation with Vaneetha, his laissez affair, if awkwardly loving, relationship with his recently divorced parents, his eerily incestuous proclivities towards his older sister, and, more chiefly, his uncertain life trajectory.

Dwight’s father, a commodities trader, plays the perfect foil to Dwight’s sister, a leftist inclining anthropologist. His mother being an Episcopalian vegetarian adds a similarly whacky layer to the already comic plot. So, it is finally his mother who sagaciously notes of the city that “you can become more inert than you notice. You can mistake the city’s commotion for your own.”

Dwight has something to chew over.

A fast approaching prep school reunion also inserts an element of urgency into Dwight’s predicament. Impetuously, he decides to fly to Ecuador to visit an old prep school classmate named Natasha, an intelligent, leggy Belgian who is the possessor of great pulchritude. The excursion, moreover, doubles as an excuse to experience the unfettered effects of Abulinix. Dwight then ends up in an Ecuadorian jungle with a native guide and a Belgian Argentine named Brigid who, coincidently, happens to be a doctoral student in anthropology with socialist leanings.

All this leads to an historical primer on the social externalities of Neo-imperialist aspirations and what, as a consequence, they excrete on benighted third world denizens. Little -- though admittedly just enough -- is said about the pervading emptiness of modern society’s secular materialism; the inaudibly incessant hum of purportedly time-saving technology, enveloping any meaningful sense of identity. Little is said of this because, I think, Kunkel was attempting to convey an astutely counterintuitive argument regarding something else.

First, concerning our choices and their concomitant freedoms, Kunkel’s protagonist says:

The deus ex machina, an Edenic folic in tropical bucolic with an ersatz Eve and apple, substituted for with a tomate de arbol, strains credulity when Dwight, with chemical-induced alacrity, signs up to serve in the fight for Global Justice. Where it not so swift and incongruous, Dwight’s decision could have at least been compelling.

Although, to be fair, Kunkel paints with broad strokes competently, and is even able to deliver a pointillist’s accuracy with impressionistic accounts. For example, even though I’m not clearly sold on Dwight’s conversion, this passage seems apt:

Dwight, meanwhile, becomes an endearing and charming character with a singularly unique voice.

Despite finding it clumsy and misshapen to begin with, Indecision turned out to be a terrifically appealing read as it worn on. Dwight’s innocence and charisma are undeniable, and the structure of the novel integrates his relative progress adeptly. Kunkel’s prose, equal parts circuitous erudition and Hemmingwayesque succinctness, begins somewhat flat and too-pleased with its own cleverness, while eventually cresting to a terse, cause-and-effect essentialism that allows this type of crafty precocity not to dwarf the narrator. At times, Kunkel was in danger of breaching that Chinese Wall between the reader and himself. Dwight is rightly permitted these breaches but the author isn’t.

Altogether, Kunkel’s bildungsroman introduces the reader to an intriguing and not easily forgettable character in Dwight, a character trying and failing to make his decisions matter to the world, when, in the end, they should matter to him.

Our aforementioned hapless narrator suffers from abulia, “Loss or impairment of the ability to make decisions or act independently”, a fittingly postmodern condition which, fittingly enough, has a postmodern biomedical cure, namely the drug Abulinix. So racked with indecision Dwight is that he’s resorted to flipping a coin to determine his actions – yet somehow still ends up feeling ambivalent. The root of this irresolution, it can be gleaned, is Dwight’s overall sense that, with the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, liberal capitalism seems ineluctably directionless, with no end in sight, or impedance in path, and certainly no morality at its core. All this seems to imply that his particular life is without consequence.

Wryly glomming over what his maybe-possibly-girlfriend Vaneetha has just said, Dwight has resigned himself to being just another cliché:

I knew she was right. It wasn’t very unusual for me to lie awake at night feeling like a scrap of sociology blown into its designated corner of the world. But knowing the clichés are clichés doesn’t help you to escape them. You still have to go on experiencing your experience as if no one else has ever done it.And then there is the mise en scene in which Dwight generally retreats to: New York City, Chambers St., with four other unambitious yet overeducated twenty-somethings cocooned in an atmosphere of eternal adolescence and irresponsibility. They wear their cultivated infantilism like a badge of honor; “Out of everybody we knew our immaturity was best-preserved, we dressed worst and succeeded least professionally.” Kunkel evokes a sentiment that is ubiquitous to this modern condition -- that of the young professional trying to evolve in a culture obsessed with youthfulness. But beyond the Chambers St. windows existed another world Dwight is understandably wary of:

Outside was the streaming traffic, the money bazaar, the trash-distributing winds with their careerist velocities. And here inside Chambers St. was the cozy set of underachievers.Martin Heidegger show’s up disguised as Otto Knittel, a philosopher whose book Dwight is unhurriedly reading. One of the intuitive aphorisms in Der Gebrauch der Freiheit – or The Uses of Freedom – is “Procrastination is our substitute for immortality” because “we behave as if we have no shortage of time.” And who of us hasn’t felt the tugging in-temporality of procrastination? As such, Kunkel infuses Dwight with a Socratic inquisitiveness that is both witty and naïve. Dwight is never without an ironic turn of phrase and -- though, I suppose, this may have been Kunkel’s aim -- isn’t as guileless as he professes.

When one of Dwight’s roommates, a putative medical student, offers him Abulinix for his indecision, Dwight contains his enthusiasm, since an otherwise decisive yes would disqualify him. But it’s a clinical trial and likely side-effects are bound to be prohibitive to his taking the drug, right? No. Dwight dives in headlong hoping, in the process, to figure out his ‘romantico-sexual’ situation with Vaneetha, his laissez affair, if awkwardly loving, relationship with his recently divorced parents, his eerily incestuous proclivities towards his older sister, and, more chiefly, his uncertain life trajectory.

Dwight’s father, a commodities trader, plays the perfect foil to Dwight’s sister, a leftist inclining anthropologist. His mother being an Episcopalian vegetarian adds a similarly whacky layer to the already comic plot. So, it is finally his mother who sagaciously notes of the city that “you can become more inert than you notice. You can mistake the city’s commotion for your own.”

Dwight has something to chew over.

A fast approaching prep school reunion also inserts an element of urgency into Dwight’s predicament. Impetuously, he decides to fly to Ecuador to visit an old prep school classmate named Natasha, an intelligent, leggy Belgian who is the possessor of great pulchritude. The excursion, moreover, doubles as an excuse to experience the unfettered effects of Abulinix. Dwight then ends up in an Ecuadorian jungle with a native guide and a Belgian Argentine named Brigid who, coincidently, happens to be a doctoral student in anthropology with socialist leanings.

All this leads to an historical primer on the social externalities of Neo-imperialist aspirations and what, as a consequence, they excrete on benighted third world denizens. Little -- though admittedly just enough -- is said about the pervading emptiness of modern society’s secular materialism; the inaudibly incessant hum of purportedly time-saving technology, enveloping any meaningful sense of identity. Little is said of this because, I think, Kunkel was attempting to convey an astutely counterintuitive argument regarding something else.

First, concerning our choices and their concomitant freedoms, Kunkel’s protagonist says:

But my tastes, my interests, my relationships and beliefs are all really mediocre and typical… And so as of today what I’ve decided with utter decisiveness is just to resign my self to mediocrity and being totally clichéd.Therefore, to embrace mediocrity, to resigns ones life to low expectations, is to accept life for what it is, contingency, absurdity, irrelevance. Since Dwight believes “it’s going to be ugly if at forty-two there’s still this like holy grail I’m hoping to trip over.” Here Kunkel renders, realistically, the common realization that one must pack-up his hopes and dreams and submit to the imperatives of the ‘real’-world. Dwight goes on to joke that a career as motivational speaker on the topic of mediocrity would be the next logical extension. Imagining himself at a lectern, Dwight admonishes thusly:

Our life sucks only because we wish it didn’t meanwhile we morally betray the world’s laboring and unemployed poor people in the nation of Ecuador and elsewhere by our failure to enjoy the fruits and nuts of our privileged consumer lifestyle. We have to be happy with this arrangement, so that some one can be.Understandably, this sounds grim worldview. Yet Kunkel is coming another-way-round to make his argument. The trek in the Jungle, the primer in political economy, the chemical effects of Abulinix and other hallucinogenic miscellany, contribute to Dwight’s awareness of his choices and their concomitant freedoms. Just as he is free to choose the beige, existentially barren conveyor-belt to a consequence-free modernity, he is likewise free to choose a thankless and peripatetic existence of little to no remuneration fighting the Neoliberal hegemony. But exactly how Kunkel arrives to this conclusion is less persuasive than one would hope, and even less convincing than Kunkel himself lets on.

The deus ex machina, an Edenic folic in tropical bucolic with an ersatz Eve and apple, substituted for with a tomate de arbol, strains credulity when Dwight, with chemical-induced alacrity, signs up to serve in the fight for Global Justice. Where it not so swift and incongruous, Dwight’s decision could have at least been compelling.

Although, to be fair, Kunkel paints with broad strokes competently, and is even able to deliver a pointillist’s accuracy with impressionistic accounts. For example, even though I’m not clearly sold on Dwight’s conversion, this passage seems apt:

I had the other tomate de arbol in my hand. Gently I started peeling it. “Ah fuck, how will we ever be happy again, Brigid? I was afraid of this happening.” I sliced the skin off the fruit in red-yellow-green scabs. But this was only on autopilot and beneath or through the careless actions of my hands I was looking at something else. It was like flying over water and then when you looked down the ocean the skim of mirror was yanked off, so that the water became transparent, and there the sea was filled with what you knew had always been there: the rubbery gardens and drowned mountains, the creatures from plankton up to nekton, the swimming bodies and the unburied skeletons, and now you—or I—I saw it all at once. And so in the fucked-up San Pedrified way the entire world system of Neoliberal capitalism disclosed itself to me, and I felt somewhat grim.

Dwight, meanwhile, becomes an endearing and charming character with a singularly unique voice.

Despite finding it clumsy and misshapen to begin with, Indecision turned out to be a terrifically appealing read as it worn on. Dwight’s innocence and charisma are undeniable, and the structure of the novel integrates his relative progress adeptly. Kunkel’s prose, equal parts circuitous erudition and Hemmingwayesque succinctness, begins somewhat flat and too-pleased with its own cleverness, while eventually cresting to a terse, cause-and-effect essentialism that allows this type of crafty precocity not to dwarf the narrator. At times, Kunkel was in danger of breaching that Chinese Wall between the reader and himself. Dwight is rightly permitted these breaches but the author isn’t.

Altogether, Kunkel’s bildungsroman introduces the reader to an intriguing and not easily forgettable character in Dwight, a character trying and failing to make his decisions matter to the world, when, in the end, they should matter to him.

Art and the Critic: Part 2

It should only make sense, then, to anticipate the coming push-back against the preponderance of adulation the Canadian indie-scene has been the object of lately. As groups like Arcade Fire, New Pornographers, Dears, Stars, Metric, The Stills, Tegan and Sara (just to name a tendentious few) are lauded over, saturation of the all things indie-Canadiana will likely wake mordant detractors from their dogmatic slumber. Moreover, the general truncation of necessary criticism and the ascendancy of less than talented, but more efficiently marketed, apparatchiks won’t help matters.

Yet this outcome is to be expected. Industry has historically been canny at co-opting and digesting the Nouvelle Vague. However, those with better taste cannot be seen to enjoy what, all of a sudden, becomes universally accepted. Public sentiment therefore acts as a type of irrelevance barometer from which the critic can gauge and then, from this analysis, take leave from the banality of groupthink. A critic, thus, finds his niche in the oppositional judgments of what standards of taste currently prevail, or failing those, which should. The piquant irony is that the critic is most often the one who helped expound prevailing orthodoxies of taste. This ambivalence betrays a disjunction.

In some top-self publications this disjunction has shown itself. Writing in Stylus, an online publication of music and film criticism, Ian Mathers has a few curt things to say about indie music, even mentioning some bands of Canadian extraction:

Mathers’s concern arises out of a reprisal of You Forgot it in People (YFIIP), which he likens to someone unwittingly receiving a golden shower and being told it was rain; and which placed 7th on Stlyus’s own top 50 of 2000-2005. So maybe he just disagrees with his colleagues’ taste, and that’s reasonable; but then in the reader-response section Mathers goes on to say,

Which would be true had we the empirical evidence. Mathers, then, is not only questioning the psychological motives of those who may be strong believers of YFIIP, he’s also throwing into doubt Stylus’s methodology or, more importantly, credibility in making Best-of lists altogether. What stock should we place in Stylus if their seventh significant album (out of a list of fifty) of the last five years has ‘thin’ support on the ground?

And this may be the case. Mathers may be right. But the weight of evidence supports a contrary conclusion: That Mathers just doesn’t like YFIIP while nearly everyone else at his publication does.

Indeed there is nothing wrong with Mathers distaste for Broken Social Scene’s aesthetic meandering, or his sentiment that ‘most people are bored by this sort of music’. Mathers criticism, although, seems to want to have it both ways. So the right brain is hearing it and saying it ‘still sounds like every other hotly tipped mess’, but the left brain is saying its ‘aimless’and ‘structurally it’s a mess’ and ‘aimless’. Ultimately, Mathers’s right brain should be listening to what his left brain is interpreting -- and vice versa -- that way they’d both be sated. What is aimless and structurally a mess to the left brain is novel and remarkable to the right brain, and what is ‘like every other hotly tipped mess’ to the right brain would please the autocracy and desire for familiarity of the left brain. (This metaphor has been unduly stretched)

Insofar as Mathers is exasperated by Broken Social Scene stylistic muddle, he is equally, if not more so, exasperated by the encomiums heaped on YFIIP. Here -- channeling Thalia, our muse of sarcasm -- is Mathers on this score:

It is fairly clear that Mathers’s distaste for Broken Social Scene is in part related to the genuflecting praise they receive. But why should it be any other way?

If reviews come out nem con in the favor of a particular artist and, subsequently, this results in that artist’s ascension, questions of relevance logically reveal themselves. The critic now has a chance to pours scorn on the artist and, inexplicably, the audience, who end up playing useful idiots. Why should this be so?

Well, this phenomenon speaks to the rational fear of the covetous and insular critic – who, at times, is indistinguishable from a booster. (Wink) Once underground music becomes accessible to the mass culture it is somehow seen as losing its aura, pace Walter Benjamin. The mechanical reproduction of it, and its social visibility, the critic argues, degrades its authenticity. This, of course, is entirely independent of the actual creative enterprise of plying ones trade as an artist; they, no doubt, have their own demons to wrestle with. But what is essential to understand is that, in effect, the critic is saying ‘because music I, at one point, thought was culturally significant is being listened to by the lower-brow and obtusely appreciative, the music now offends my sensibilities’.

This is in fact what the critic is saying -- something we’ve all said one time or another out of covetousness for a particular cultural objet d'art only a few of our close friends were astute or privileged enough to know about first. And I would be lying if I said I didn’t bask in my cognizance when I listened to Feel Good Lost, assured that I was in the Know (with infinitesimal pockets of others) months and years before anyone else -- people I gladly turned my nose to. And yes, there was a usurped pang in my chest when someone brought up the fact that they were already listening to Broken Social Scene two months before I was -- and then there was the contained shock when they said they no longer listened to them; likely as a result of my listening to them.

So this pantomime of sophistication, that my art is better and more avant-garde than yours, is nothing if not predictable. But the assertion that just because something is popular it therefore lacks relevance is wrongheaded. (Notwithstanding democratic elections in countries saddled with dictatorships) If so, nearly all classical music, from Renaissance to Baroque to the Romantics to Contemporary Avant Garde, would have no cultural value. Bartok, Brahms, Beethoven, Mozart, Bach, and Schoenberg especially, are still relevant today -- although in markedly different ways.

And yet the detractors do make sound arguments. That popularity may be its own justification, that prefabrication and mass distribution deracinates the DIY ethic of music in general and indie rock specifically, and that loss of artistic autonomy takes away something authentic in the process are all arguments that have found no easy response. Yet at the same time these arguments raise questions that are structural and indissoluble within the context of art and commerce.

Should artists live in penury to remain authentic? Why can’t being accessible mean something more than just selling-out? Is authorial sincerity in popular art always required, or even detectable? These are all difficult questions to interrogate. But each day the artist, the critic, and the audience are doing the calculus and responding with their actions. These questions are also eternal challenges that won’t be brought to any finality, and shouldn’t hoped to be, otherwise the whole enterprise of art would lapse into solipsism. We can see the forest for the trees or we can just see the trees. I’m a big fan of the forest -- and the trees.

Yet this outcome is to be expected. Industry has historically been canny at co-opting and digesting the Nouvelle Vague. However, those with better taste cannot be seen to enjoy what, all of a sudden, becomes universally accepted. Public sentiment therefore acts as a type of irrelevance barometer from which the critic can gauge and then, from this analysis, take leave from the banality of groupthink. A critic, thus, finds his niche in the oppositional judgments of what standards of taste currently prevail, or failing those, which should. The piquant irony is that the critic is most often the one who helped expound prevailing orthodoxies of taste. This ambivalence betrays a disjunction.

In some top-self publications this disjunction has shown itself. Writing in Stylus, an online publication of music and film criticism, Ian Mathers has a few curt things to say about indie music, even mentioning some bands of Canadian extraction:

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with indie music, and if that’s all you listen to then yes, this or the Arcade Fire probably sounds as catchy as all get out – but to the average person out there who doesn’t (for example) read Stylus, this still sounds like every other hotly tipped mess that most people don’t like, not because we privileged few have “better” “taste” or something equally smug, but just because most people are bored by this sort of music. It is not a badge of superiority or mark of inferiority to feel differently. But it would certainly be easier for others to tolerate if this was actually any good.One has to concede that indie-rock tends to be an incestuous claque of the cognizant; Mathers’s point should be taken. I’m not convinced, however, that ‘most people are bored by this sort of music’ or that it’s less tolerable because it’s not good. (Broken Social Scene is selling to exactly the type of people it shouldn’t be selling to)

Mathers’s concern arises out of a reprisal of You Forgot it in People (YFIIP), which he likens to someone unwittingly receiving a golden shower and being told it was rain; and which placed 7th on Stlyus’s own top 50 of 2000-2005. So maybe he just disagrees with his colleagues’ taste, and that’s reasonable; but then in the reader-response section Mathers goes on to say,

I'm a strong believer in the idea that if you love an album, nothing anyone says should (or can) count against that. I also think a fair number of the people who hyped this record don't fall into that category, though, and that genuine love for the whole thing is a little thinner on the ground than some would claim.

Which would be true had we the empirical evidence. Mathers, then, is not only questioning the psychological motives of those who may be strong believers of YFIIP, he’s also throwing into doubt Stylus’s methodology or, more importantly, credibility in making Best-of lists altogether. What stock should we place in Stylus if their seventh significant album (out of a list of fifty) of the last five years has ‘thin’ support on the ground?

And this may be the case. Mathers may be right. But the weight of evidence supports a contrary conclusion: That Mathers just doesn’t like YFIIP while nearly everyone else at his publication does.

Indeed there is nothing wrong with Mathers distaste for Broken Social Scene’s aesthetic meandering, or his sentiment that ‘most people are bored by this sort of music’. Mathers criticism, although, seems to want to have it both ways. So the right brain is hearing it and saying it ‘still sounds like every other hotly tipped mess’, but the left brain is saying its ‘aimless’and ‘structurally it’s a mess’ and ‘aimless’. Ultimately, Mathers’s right brain should be listening to what his left brain is interpreting -- and vice versa -- that way they’d both be sated. What is aimless and structurally a mess to the left brain is novel and remarkable to the right brain, and what is ‘like every other hotly tipped mess’ to the right brain would please the autocracy and desire for familiarity of the left brain. (This metaphor has been unduly stretched)

Insofar as Mathers is exasperated by Broken Social Scene stylistic muddle, he is equally, if not more so, exasperated by the encomiums heaped on YFIIP. Here -- channeling Thalia, our muse of sarcasm -- is Mathers on this score:

This is it? This is the great revolution? This is what topped the critics’ charts, inspired a million rapturous articles and blog posts and personal testimonies? This? This rancid stew of sour indie self-regard, the disingenuous assurance that no, now we’re making pop music (so for once it’ll be good, lol)

It is fairly clear that Mathers’s distaste for Broken Social Scene is in part related to the genuflecting praise they receive. But why should it be any other way?

**

If reviews come out nem con in the favor of a particular artist and, subsequently, this results in that artist’s ascension, questions of relevance logically reveal themselves. The critic now has a chance to pours scorn on the artist and, inexplicably, the audience, who end up playing useful idiots. Why should this be so?

Well, this phenomenon speaks to the rational fear of the covetous and insular critic – who, at times, is indistinguishable from a booster. (Wink) Once underground music becomes accessible to the mass culture it is somehow seen as losing its aura, pace Walter Benjamin. The mechanical reproduction of it, and its social visibility, the critic argues, degrades its authenticity. This, of course, is entirely independent of the actual creative enterprise of plying ones trade as an artist; they, no doubt, have their own demons to wrestle with. But what is essential to understand is that, in effect, the critic is saying ‘because music I, at one point, thought was culturally significant is being listened to by the lower-brow and obtusely appreciative, the music now offends my sensibilities’.

This is in fact what the critic is saying -- something we’ve all said one time or another out of covetousness for a particular cultural objet d'art only a few of our close friends were astute or privileged enough to know about first. And I would be lying if I said I didn’t bask in my cognizance when I listened to Feel Good Lost, assured that I was in the Know (with infinitesimal pockets of others) months and years before anyone else -- people I gladly turned my nose to. And yes, there was a usurped pang in my chest when someone brought up the fact that they were already listening to Broken Social Scene two months before I was -- and then there was the contained shock when they said they no longer listened to them; likely as a result of my listening to them.

So this pantomime of sophistication, that my art is better and more avant-garde than yours, is nothing if not predictable. But the assertion that just because something is popular it therefore lacks relevance is wrongheaded. (Notwithstanding democratic elections in countries saddled with dictatorships) If so, nearly all classical music, from Renaissance to Baroque to the Romantics to Contemporary Avant Garde, would have no cultural value. Bartok, Brahms, Beethoven, Mozart, Bach, and Schoenberg especially, are still relevant today -- although in markedly different ways.

And yet the detractors do make sound arguments. That popularity may be its own justification, that prefabrication and mass distribution deracinates the DIY ethic of music in general and indie rock specifically, and that loss of artistic autonomy takes away something authentic in the process are all arguments that have found no easy response. Yet at the same time these arguments raise questions that are structural and indissoluble within the context of art and commerce.

Should artists live in penury to remain authentic? Why can’t being accessible mean something more than just selling-out? Is authorial sincerity in popular art always required, or even detectable? These are all difficult questions to interrogate. But each day the artist, the critic, and the audience are doing the calculus and responding with their actions. These questions are also eternal challenges that won’t be brought to any finality, and shouldn’t hoped to be, otherwise the whole enterprise of art would lapse into solipsism. We can see the forest for the trees or we can just see the trees. I’m a big fan of the forest -- and the trees.

Sunday, October 30, 2005

Broken Social Scene: Part 1

If your ecumenical tent encompasses the likes of Metric’s Emily Haines and James Shaw, Evan Cranley and Amy Millan of the Stars, and Leslie Feist of Let it Die fame, among others, then the company you keep and the music you create has to be thoroughly layered and unflinchingly collaborative. This is to say nothing of the music’s originality. So, as it happens, there is such a thing, and said music is put together by the Toronto collective-cum-network of indie rockers dubed Broken Social Scene -- who manage to allay our fears about the psychological pathologies of communes. The Utopia hasn’t yet faltered. Since they’re a diverse outfit, they have the flexibility to pursue side projects while still maintaining the ethos of Broken Social Scene the idea. (It doesn't hurt that most of these side projects are in some way affliated with Arts and Crafts records, a boutique label created by the band's doyen, Kevin Drew.)

And this idea has been received with near universal praise. (Fawning reviews in all the major trade publications, the 2003 Juno for Best Alternative album, etc.) Taken literally, the group is a pastiche of each individual’s particular aesthetic bent -- Metric’s tightly shorn arrangements and acerbic lyricism; the lush yet literate extravagance of Stars; and (not a comprehensive list) Leslie Feist and Jason Collett’s soul and sincerity and earnest. (And yet the list goes on.) The ‘supergroup’ -- as they’ve been flatteringly referred to; as if this write up weren’t itself obsequious -- took its initial material form in 1997, fronted by Kevin Drew and Brendan Canning. It was only in about 2002 that I was caught up to speed on Feel Good Lost(2001) and You Forgot it in People(2003), which were both phenomenal if not epiphenomenal and subsequently seared into my indispensable hippocampus.

All this is just to say that I picked up Broken Social Scene’s eponymous new LP. To begin with, the art that adorns the cd’s packaging cover is a winsomely contrived cityscape back-dropped by a vermillion, almost fiery, sky. A three section fold-out stores two disc; the main disc and a bonus (i.e. limited edition) disc featuring songs equally up to rigor to appear on the first. The booklet, like the casing, is similarly artful, with the faux-jejune scribblings of a ten-year old boy and the epigrammatic tags of the unabashedly guileless -- for instance, the wry declaration “We hate your hate” can be read on the inside jacket. Though now we should turn to the music, lest this devolve into a tedious account of the all particulars.

The current LP is in many ways, both stylistically and tonally (atonally as well) akin to Feel Good Lost, mostly instrumental and atmospheric in tone. Case in point is the track ‘Feel Good Lost Reprise’ on the bonus cd. But where it departs from Feel Good Lost, it collides with You Forgot it in People (YFIIP) in its reflexive meandering. The acoustics, horns and base line -- as well as tambourines -- that open ‘Our faces split the coast in half’ harkens back to ‘Pacific Theme’ off YFIIP, albeit in a less sleepy and more enthused way. In plosive restraint, Feist’s fixed vocals turn out to punctuate a palimpsest of a song -- that may or may not feature the aural yawn of a cello. Feist’s lilting accompaniments are once again prominent in ‘7/4 (shoreline)’ as Brendan and Kevin et al. warm over the track with endearing falsettos. Lead guitars duel with frenetic drums while late arriving horns portend an impending collapse.

The rest album is an untidy and unstudied mash of experientialism, a bric-a-brac of orchestral cacophony; ponderously frustrating, but not too much so, yet axiomatic and ephemeral at once. The sound is decidedly arty and pop and abides to a sensibility producer Dave Newfeld also brought to YFIIP. Newfeld has show peerless technical proficiency in making blunt, disparate parts reflect light while intergrating recondite instrumentals and melodies into serviceable coherence. It's a creative match with serious fecundity.

‘Superconnected’, with its distorted and majestic keys and angst-laden, bleating vocals, ‘Hotel’, a clavicle jutting trip with nascent pretensions of Synth and Soul, and ‘It’s all gonna break’, a conventional though extend (as in nine minutes) indie-rock narrative that may be trying to say something, count as other notable mentions on this canonical opus.

The ironically titled ‘Major label debut’ is by leap and bounds my favorite of the whole lot. And that is no small feat. It begins ethereally enough with deliberately strummed acoustic guitars (and possibly a harpsichord) foreground by a paradoxically soft snare drum and heavy bass drums that mimic heartbeats but don’t overwhelm the ambience. Kevin Drew’s voice emerges -- along with the sliding atonal shiver of the cymbal -- filled with the insouciance of an autumnal night still kind enough to permit Bermudas. It’s positively weightless. An incantatory tone is struck: ‘I’m just coming here to come down / I can be here / and I can move town / Put my suits onto the guest lists / summer passport became weightless.’ Then the expletive chorus ‘I’m all fucked up’ is reverentially, and all-too-hypnotically, sung as the drums pick-up in a mannered and incremental cadence, the strings dovetailing into a fitting denouement. (Actually, the chorus could be as benign as "I'm all hooked-up"but it's too inaudible to tell, and beside the point anyway.)

The song, pastoral and unambitious, is the high-art equivalent of an early Matisse: not exactly challenging, but thoughtfully and artistically scrupulous with due respect to color, space, mood, and intellect. And this, I think, can describe one of Broken Social Scene’s aesthetic virtues. The other, of course, is the primary unintelligibility of some of their work, as if challenging the listener to engage the morass. Unfortunately this does lead to frustration and is even liable to alienate the listener. Though like any challenging piece of art, the pleasure is in accessing the implicit emotive aspect of the work, thus framing it with the coherence you see fit. Each song offers something new on each successive hearing.

Having moved from the more melancholic and aimless pessimism of Feel Good Lost, and keenly incorporating the technique of chaotic polish from YFIIP, their third album -- despite not being as virtuosic-ally competent as YFIIP -- places itself well in the Broken Social Scene oeuvre.

But critical praise always brings along her ugly, fraternal twin. When critics hoist artists onto a vaunted pedestal, it is usually them who double back and commit a punitive revisionism.

And this idea has been received with near universal praise. (Fawning reviews in all the major trade publications, the 2003 Juno for Best Alternative album, etc.) Taken literally, the group is a pastiche of each individual’s particular aesthetic bent -- Metric’s tightly shorn arrangements and acerbic lyricism; the lush yet literate extravagance of Stars; and (not a comprehensive list) Leslie Feist and Jason Collett’s soul and sincerity and earnest. (And yet the list goes on.) The ‘supergroup’ -- as they’ve been flatteringly referred to; as if this write up weren’t itself obsequious -- took its initial material form in 1997, fronted by Kevin Drew and Brendan Canning. It was only in about 2002 that I was caught up to speed on Feel Good Lost(2001) and You Forgot it in People(2003), which were both phenomenal if not epiphenomenal and subsequently seared into my indispensable hippocampus.

All this is just to say that I picked up Broken Social Scene’s eponymous new LP. To begin with, the art that adorns the cd’s packaging cover is a winsomely contrived cityscape back-dropped by a vermillion, almost fiery, sky. A three section fold-out stores two disc; the main disc and a bonus (i.e. limited edition) disc featuring songs equally up to rigor to appear on the first. The booklet, like the casing, is similarly artful, with the faux-jejune scribblings of a ten-year old boy and the epigrammatic tags of the unabashedly guileless -- for instance, the wry declaration “We hate your hate” can be read on the inside jacket. Though now we should turn to the music, lest this devolve into a tedious account of the all particulars.

The current LP is in many ways, both stylistically and tonally (atonally as well) akin to Feel Good Lost, mostly instrumental and atmospheric in tone. Case in point is the track ‘Feel Good Lost Reprise’ on the bonus cd. But where it departs from Feel Good Lost, it collides with You Forgot it in People (YFIIP) in its reflexive meandering. The acoustics, horns and base line -- as well as tambourines -- that open ‘Our faces split the coast in half’ harkens back to ‘Pacific Theme’ off YFIIP, albeit in a less sleepy and more enthused way. In plosive restraint, Feist’s fixed vocals turn out to punctuate a palimpsest of a song -- that may or may not feature the aural yawn of a cello. Feist’s lilting accompaniments are once again prominent in ‘7/4 (shoreline)’ as Brendan and Kevin et al. warm over the track with endearing falsettos. Lead guitars duel with frenetic drums while late arriving horns portend an impending collapse.

The rest album is an untidy and unstudied mash of experientialism, a bric-a-brac of orchestral cacophony; ponderously frustrating, but not too much so, yet axiomatic and ephemeral at once. The sound is decidedly arty and pop and abides to a sensibility producer Dave Newfeld also brought to YFIIP. Newfeld has show peerless technical proficiency in making blunt, disparate parts reflect light while intergrating recondite instrumentals and melodies into serviceable coherence. It's a creative match with serious fecundity.

‘Superconnected’, with its distorted and majestic keys and angst-laden, bleating vocals, ‘Hotel’, a clavicle jutting trip with nascent pretensions of Synth and Soul, and ‘It’s all gonna break’, a conventional though extend (as in nine minutes) indie-rock narrative that may be trying to say something, count as other notable mentions on this canonical opus.

The ironically titled ‘Major label debut’ is by leap and bounds my favorite of the whole lot. And that is no small feat. It begins ethereally enough with deliberately strummed acoustic guitars (and possibly a harpsichord) foreground by a paradoxically soft snare drum and heavy bass drums that mimic heartbeats but don’t overwhelm the ambience. Kevin Drew’s voice emerges -- along with the sliding atonal shiver of the cymbal -- filled with the insouciance of an autumnal night still kind enough to permit Bermudas. It’s positively weightless. An incantatory tone is struck: ‘I’m just coming here to come down / I can be here / and I can move town / Put my suits onto the guest lists / summer passport became weightless.’ Then the expletive chorus ‘I’m all fucked up’ is reverentially, and all-too-hypnotically, sung as the drums pick-up in a mannered and incremental cadence, the strings dovetailing into a fitting denouement. (Actually, the chorus could be as benign as "I'm all hooked-up"but it's too inaudible to tell, and beside the point anyway.)

The song, pastoral and unambitious, is the high-art equivalent of an early Matisse: not exactly challenging, but thoughtfully and artistically scrupulous with due respect to color, space, mood, and intellect. And this, I think, can describe one of Broken Social Scene’s aesthetic virtues. The other, of course, is the primary unintelligibility of some of their work, as if challenging the listener to engage the morass. Unfortunately this does lead to frustration and is even liable to alienate the listener. Though like any challenging piece of art, the pleasure is in accessing the implicit emotive aspect of the work, thus framing it with the coherence you see fit. Each song offers something new on each successive hearing.

Having moved from the more melancholic and aimless pessimism of Feel Good Lost, and keenly incorporating the technique of chaotic polish from YFIIP, their third album -- despite not being as virtuosic-ally competent as YFIIP -- places itself well in the Broken Social Scene oeuvre.

But critical praise always brings along her ugly, fraternal twin. When critics hoist artists onto a vaunted pedestal, it is usually them who double back and commit a punitive revisionism.

Friday, September 23, 2005

The State of the Nation

If one was so inclined -- and there are many that are -- one would get the impression that God is exercising a bit of his wrath. And he doesn’t seem to be letting up. Scoff if you must at Revelations, at End of Days and Armageddon, at the Second Coming or the four horsemen of the apocalypse, a cynic can’t deny the inherent eeriness of this past summer.

The city of Toronto officially acquired the all-too-realistic nickname Smoke City, literally becoming an emissions and carbon monoxide swelter. Gas prices -- or where to begin with gas prices! -- have defied comprehension while supply, instead of diminishing, has increased marginally. How to explain this discrepancy has everything to do with the psychological motive of fear—or more clearly, speculative fear. All summer long investors have been afraid of Iraq, of reforms in Saudi Arabia and Egypt and Lebanon and how hegemony over oil is diminishing.

Similarly, investors have been afraid of China and Indian, both evolving economies that will soon eclipse the U.S economy. And somehow dollar-per-barrel became the demotic tongue of all. $30 dpb sometime in 2004, it was ridiculous to think, when they joked, that oil would reach $50 dpb. When it reached $70 dpb and looked as though it wasn’t planning on moving much, either up or down, the grousing and the bristling was no longer inaudible. Welcome to the Information Age, truly.

The Markets have learned to ‘price-in’ anticipated imbalances, and have subsequently begun operating on ‘attitudes’ and sentiments. A sentence from a Federal Reserve press release is parsed exegetically and the Markets move. A storm report from the The National Hurricane Center is issued and the Markets move. We are so awash with technical information, often times contradictory and conflicting, that we’ve settled into a catatonic paralysis. The risk premium, which is necessarily a portent for scarcity, or worse, collapse, has priced-up the one commodity that is sine non qua to the world economy: Oil.

It turns out that fear isn’t only a serviceable tactic in terrorism or electoral politics but also profit-taking. As cringe-worthy as arguments for nationalization of vital oil resources are, the notion has once again become far more appealing than the current scenario. Rita will wreck its havoc and the United States will be writing another $200 billion dollar cheque – on top of the $200 billion for Katrina and the $200 billion for Iraq; which isn’t even to speak of billions for Medicaid/Medicare. And although this financing is long-term, the horizon is closing in fast and liabilities are mounting. I pray for the U.S economy; if only for the fate of the Canadian economy.

The city of Toronto officially acquired the all-too-realistic nickname Smoke City, literally becoming an emissions and carbon monoxide swelter. Gas prices -- or where to begin with gas prices! -- have defied comprehension while supply, instead of diminishing, has increased marginally. How to explain this discrepancy has everything to do with the psychological motive of fear—or more clearly, speculative fear. All summer long investors have been afraid of Iraq, of reforms in Saudi Arabia and Egypt and Lebanon and how hegemony over oil is diminishing.

Similarly, investors have been afraid of China and Indian, both evolving economies that will soon eclipse the U.S economy. And somehow dollar-per-barrel became the demotic tongue of all. $30 dpb sometime in 2004, it was ridiculous to think, when they joked, that oil would reach $50 dpb. When it reached $70 dpb and looked as though it wasn’t planning on moving much, either up or down, the grousing and the bristling was no longer inaudible. Welcome to the Information Age, truly.

The Markets have learned to ‘price-in’ anticipated imbalances, and have subsequently begun operating on ‘attitudes’ and sentiments. A sentence from a Federal Reserve press release is parsed exegetically and the Markets move. A storm report from the The National Hurricane Center is issued and the Markets move. We are so awash with technical information, often times contradictory and conflicting, that we’ve settled into a catatonic paralysis. The risk premium, which is necessarily a portent for scarcity, or worse, collapse, has priced-up the one commodity that is sine non qua to the world economy: Oil.

It turns out that fear isn’t only a serviceable tactic in terrorism or electoral politics but also profit-taking. As cringe-worthy as arguments for nationalization of vital oil resources are, the notion has once again become far more appealing than the current scenario. Rita will wreck its havoc and the United States will be writing another $200 billion dollar cheque – on top of the $200 billion for Katrina and the $200 billion for Iraq; which isn’t even to speak of billions for Medicaid/Medicare. And although this financing is long-term, the horizon is closing in fast and liabilities are mounting. I pray for the U.S economy; if only for the fate of the Canadian economy.

Thursday, September 15, 2005

The History of Love

Leo Grusky’s eccentricities are those of a warped personality, at peace with silence and loneliness as he is with old age and what it has done to his body. Leo Grusky is also a tragic soul -- bereft of the friends from his idyllic childhood, the family of his native town, and the woman he will love forever.

In 1938, as the Germans roll through Poland, Leo is forced into hiding, assured by his parents that they will return for him. When it is obvious that they will not, that they have died at the hands of the Nazis, Leo flees to America in search of his sweetheart Alma Meremenski -- who has also been driven to seek refuge in America. But when he arrives, Alma -- who thought he’d perished in Poland -- is set to marry another man.

This narrative buttresses the general premise from which the rest of the novel evolves in Nicole Krauss’s The History of Love. Since Leo is unable to marry Alma, and, similarly, never to reveal to anyone that he is the father of their child together, he settles into an unremarkable existence, shuttling from his job as a locksmith to his lonely apartment where he writes, intermittently. That Alma would be unwilling to marry her lost sweetheart and that Leo would have to spend the rest of his life both alone and denied of his son are fairly weighty assumptions for this novel to rest on. And I don’t entirely buy them.

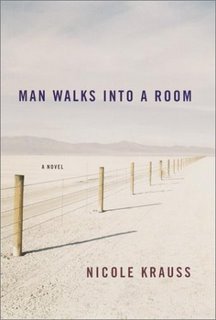

Yet Krauss once again does an excellent job creating a lithe yet deep edifice in which her characters can develop. Her first novel, A Man Walks Into a Room, was substantial while perpetrating all the sins of a vacuum. (Though, that was essentially the point; having lost his memory, the reader was tasked to fill in the blanks for Samson Greene.) The History of Love, however, asks the reader for too much credulity.

Leo Gursky has written a book with the eponymous title of the novel regarding the story of his and Alma’s love. Before leaving Slonim, Poland, Leo places The History of Love in an envelope and gives it to his friend Zvi Litvinoff for safe keeping. When the baleful aspirations of the Nazis become apparent, Zvi leaves for Chile, with envelop in-hand, to stay with a cousin. In the ensuing years, resigned to the fact that his friend Leo Gursky has mostly likely died, Zvi, encouraged mainly by his wife, publishes The History of Love under his name. The History of Love is an historical artifact that enmeshes another character in the novel, Alma Singer, whose father names her after the main character.

Alma is curious to find out, after her father dies, the significance of this novel, and whether the Alma Meremenski in the novel is real. I can’t say that I enjoyed this novel more than A Man Walks Into a Room, but it does have a charm -- Leo Gursky particularly.

While not necessarily imbuing an overly heart-rending wistfulness in him, Krauss deftly conveys Leo’s empathic qualities -- his thoughtfulness, his warmth, and his asceticism. There were also passages where Leo was unqualifiedly funny; but unfortunately there weren’t nearly enough. Krauss has a wry, almost counterintuitive way with prose and parody that is refreshingly trenchant. Take for instance this excerpt, where a woman has called to ask if Leo is interested in an Art project:

In 1938, as the Germans roll through Poland, Leo is forced into hiding, assured by his parents that they will return for him. When it is obvious that they will not, that they have died at the hands of the Nazis, Leo flees to America in search of his sweetheart Alma Meremenski -- who has also been driven to seek refuge in America. But when he arrives, Alma -- who thought he’d perished in Poland -- is set to marry another man.

This narrative buttresses the general premise from which the rest of the novel evolves in Nicole Krauss’s The History of Love. Since Leo is unable to marry Alma, and, similarly, never to reveal to anyone that he is the father of their child together, he settles into an unremarkable existence, shuttling from his job as a locksmith to his lonely apartment where he writes, intermittently. That Alma would be unwilling to marry her lost sweetheart and that Leo would have to spend the rest of his life both alone and denied of his son are fairly weighty assumptions for this novel to rest on. And I don’t entirely buy them.

Yet Krauss once again does an excellent job creating a lithe yet deep edifice in which her characters can develop. Her first novel, A Man Walks Into a Room, was substantial while perpetrating all the sins of a vacuum. (Though, that was essentially the point; having lost his memory, the reader was tasked to fill in the blanks for Samson Greene.) The History of Love, however, asks the reader for too much credulity.

Leo Gursky has written a book with the eponymous title of the novel regarding the story of his and Alma’s love. Before leaving Slonim, Poland, Leo places The History of Love in an envelope and gives it to his friend Zvi Litvinoff for safe keeping. When the baleful aspirations of the Nazis become apparent, Zvi leaves for Chile, with envelop in-hand, to stay with a cousin. In the ensuing years, resigned to the fact that his friend Leo Gursky has mostly likely died, Zvi, encouraged mainly by his wife, publishes The History of Love under his name. The History of Love is an historical artifact that enmeshes another character in the novel, Alma Singer, whose father names her after the main character.

Alma is curious to find out, after her father dies, the significance of this novel, and whether the Alma Meremenski in the novel is real. I can’t say that I enjoyed this novel more than A Man Walks Into a Room, but it does have a charm -- Leo Gursky particularly.

While not necessarily imbuing an overly heart-rending wistfulness in him, Krauss deftly conveys Leo’s empathic qualities -- his thoughtfulness, his warmth, and his asceticism. There were also passages where Leo was unqualifiedly funny; but unfortunately there weren’t nearly enough. Krauss has a wry, almost counterintuitive way with prose and parody that is refreshingly trenchant. Take for instance this excerpt, where a woman has called to ask if Leo is interested in an Art project:

What kind of project? I asked. She said all I had to do was sit naked on a metal stool in the middle of the room and then, if I felt like it, which she was hoping I would, dip my body into a vat of kosher cow’s blood and roll on the large white sheet of paper provided.

I may be a fool but I’m not desperate. There’s only so far I’m willing to go, so I thanked her very much for the offer but said I was going to have to turn it down since I was already scheduled to sit on my thumb and rotate in accordance with the movements of the earth around the sun.Passages like these are indispensable to the novel's wit. I’m hoping that her next project will be unreservedly ironic. But Krauss is as much in her skin with comedy as she is with fraught, pithy poetics. She is not cynical about love, and it shows in her relentlessly maudlin style -- which is to countervailing effect when the deluge exacts from the reader all that is left of romanticism and empathy.

Wednesday, August 17, 2005

Aestheics

Rosemary, Heaven restores you in life:The inviting yet sinister baseline that opens Evil -- a track off Interpol’s 2004 sophomore LP Antics -- is too mesmerizing by half. The rest of the LP, which I think is solid, was greeted with tepid reviews. Surely they weren’t listening to the same album I was listening to. But yeah, good stuff! Turn on the Bright Lights, their 2002 offering, was clearly much stronger; tracks like Untitled, NYC, PDA, etc., have eerie parallels to Joy Division – an English post-punk band I’ve warmed to. Though, I can’t really see anything wrong with the aesthetics of Antics. The wan linearity of mood, an exercise in restrained impressionism, pervades through the album. Many would say it’s a recapitulation of TOTBL; and it generally is. But TOTBL was great, ergo: Antics > TOTBL? Same as?

Moving right along. At the Bodega down the way, purchasing miscellany, I was be-stilled of heart by a thoroughly indiesque Korean clerk -- likely holdin' it down while paterfamilias transacted business elsewhere. She seemed at ease with what can be ineptly described as an unguarded and unpretentious charm. I commented on her shirt since it appeared no other avenues for superfluous blather were viable, without sounding creepy or invasive of course. The shirt, black, up-against the body, fitting the way it should on a girl like her, was unremarkable, the illegible silkscreen graphics altogether uninspiring. It was only an afterthought to even actually look at the shirt, so consumed was I in fixing her a mawkish gaze. (You have to know I’m exaggerating.)

Anyway, the point is that the response to the shirt question was more interesting than the shirt itself. “The Weakerthans” she says, while continuing to catch me up to speed. Apparently they aren’t that bad. Remember Propagandhi, the Winnipeg punk outfit trafficking in agitprop par excellence? Well, The Weakerthans is Propagandhi member John K. Samson’s new (other?) gig. Presently, I’m enjoying Summer Rain and Benediction. I left to quickly and awkwardly to know whether or not said girl was feeling me, although in my experience it’s very likely that she was. (Zing!) Groups I’m enjoying: (Also) see Red House Painters, soul rending stuff.

Moving right along. At the Bodega down the way, purchasing miscellany, I was be-stilled of heart by a thoroughly indiesque Korean clerk -- likely holdin' it down while paterfamilias transacted business elsewhere. She seemed at ease with what can be ineptly described as an unguarded and unpretentious charm. I commented on her shirt since it appeared no other avenues for superfluous blather were viable, without sounding creepy or invasive of course. The shirt, black, up-against the body, fitting the way it should on a girl like her, was unremarkable, the illegible silkscreen graphics altogether uninspiring. It was only an afterthought to even actually look at the shirt, so consumed was I in fixing her a mawkish gaze. (You have to know I’m exaggerating.)

Anyway, the point is that the response to the shirt question was more interesting than the shirt itself. “The Weakerthans” she says, while continuing to catch me up to speed. Apparently they aren’t that bad. Remember Propagandhi, the Winnipeg punk outfit trafficking in agitprop par excellence? Well, The Weakerthans is Propagandhi member John K. Samson’s new (other?) gig. Presently, I’m enjoying Summer Rain and Benediction. I left to quickly and awkwardly to know whether or not said girl was feeling me, although in my experience it’s very likely that she was. (Zing!) Groups I’m enjoying: (Also) see Red House Painters, soul rending stuff.

Saturday, July 30, 2005

The Twenty-Seventh-City

The city of St. Louis, during a bizarre autumn sometime in the waning years of the 1980’s, selects S. Jammu, a Los Angles born Indian -- formally the Police commissioner of Bombay, Indian -- to succeed the city’s former police chief. The development, needless to say, is unexpected. Jammu hasn’t lived in the United States in over a decade, and that she is a woman doesn’t help matters. Unsurprisingly, the political and business community are skeptical -- the county’s benevolent advisory board, Municipal Growth, especially. And then things begin to change.

Where Jammu was once perceived as an inexperienced and inappropriate choice, she becomes a fount of civic adulations and a symbol for the New St. Louis. Members of Municipal Growth conveniently start revising their opinions of Jammu as, inexplicitly, incidences of bombings and terror related attacks are directed at either them or citizens of the city. It would only seem plausible to draw the necessary connections between Jammu’s arrival on the scene and the oddity of St. Louis being targeted by terrorists, or Indians (that is: Native Americans; an erstwhile, non-extant tribe that miraculously reassembles to terrorize the city and county of St. Louis for past pre-colonial grievances.)

No one but General Norris, a member of Municipal Growth and an unreconstructed character, smells a conspiracy afoot, implausible as this may seem. But this is with good reason: Jammu has managed to extort and blackmail nearly every prominent business and civic leader in St. Louis, amassing the necessary political and logistical power to execute her plan -- to create a real-estate appreciation in downtown St. Louis, an area, not too uncoincidentally, her mother has just recently invested considerable capital in. Nevertheless, Jammu has one final obstacle in Martin Probst, a respected contractor, a paragon of morality, and chairman of Municipal Growth.

And so begins The Twenty-Seventh City, Jonathan Franzen’s ambitious if somewhat circuitous first novel. The plot is dense, populated by a litany of characters with oscillating motives. Of the narratives, and there are many, Martin Probst’s is of primary import. Probst is best know for being the man who built the Arch, so naturally the mantel of probity rests on him while Jammu attempts, indefatigably, to break him, thus assuring her plan’s success. The campaign she wages would surely be without scruples if undertaken by any ordinary person; it is therefore that much worse that the police chief of St. Louis is behind it.

Yet Jammu isn’t your ordinary person -- or pol or public official, for that matter. She is a hardened politically militant socialist of Trotskyite bent. She is also a protégé of Indira Gandhi, a person to whom she owes much for her professional advancement in Bombay. Though, there is a strain of aimless malice in Jammu which strikes me as vapid. It is amazing how Franzen is able to masterly construct this gargantuan plot yet also skimp on his characters’ consciousness. This is particularly the case with Jammu, who is rarely, if only partially, psychologized to the extent of illumination. Insofar as she maintains a shadowy mystic to the characters in Franzen’s novel, she remains almost entirely ineffable to the reader.

Martin Probst, similarly, is fleshed out rather feebly. We understand that moral rectitude is his métier and “accomplishing things” drives him, but beyond that his rigidity and opacity become stifling—his asceticism literally frustrates the reader. Even when General Norris approaches Probst with the voluminous evidence of The Conspiracy and Jammu’s unsavory involvement in it, Martin chides the General for his outlandishness. What Franzen, in my opinion, seems to be saying of conspiracy theories -- possibly his novelistic conceit -- is that they are for ‘weaker minds.’ He says this while having elaborated on a baroque novel of conspiracy. Is this not frustrating? Was this his intention? What begins to happen to Probst, while tragic, could be construed as cathartic -- for the reader, me specifically. Martin reminds me too much of Alfred Lambert from The Corrections, a character he anticipates.

But Franzen is adept when he’s waxing political.There are overtones of Cold War critique and, as the thought strikes me now, nearly everyone is afflicted with the symptoms of a cold. This was a peculiar meme that I had first attributed to merely banal symbolism; but on further analysis it seems clear that Jammu, a committed marxist qua terrorist, represents an ideological infection, and her efforts at fomenting real-estate speculation are directed towards undermining (indulge me) the arbitrary logic of capitalism -- even if it’s only in St. Louis.

However, my understanding of this is still very shallow since, it seems, Franzen is all over the place. If it is anything, The Twenty-Seventh City is an astute commentary on the local and the political. That a small group of political and financially influential citizens can steer the course of a city, thus determining its fate, is not a new argument. Franzen, instead, offers something polemical: