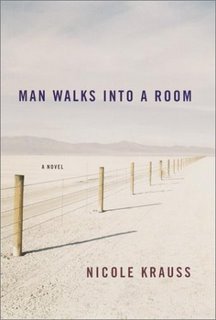

Nicole Krauss’s first novel A Man Walks Into a Room is a beautiful, poetic, lilt that is at once endearing and intellectual. Samson Greene is found wandering the Nevada desert, unknowing and unknown to authorities. Initially, law enforcement officers are doubtful if the identification that bears Samson’s name is, in fact, actually his; but it is soon confirmed that the Samson Greene aimlessly walking the Nevada desert is Samson Greene -- resident of New York, professor of English at Columbia.

To the surprise of a neurosurgeon and, later, his wife, Anna, it turns out that a tumor the size of a cherry has wiped out Samson’s entire memory – well not exactly. Samson will remember nothing of the past twenty-four years of his life once the tumor is removed; not his job, not his friends, and not, more tragically, Anna.

Recalling only the first twelve years of his life, Samson enters his new reality with timidity and awe. The geopolitical tête - à – tête that was the Cold War is over; an older and more intoxicated Billy Joel appears puzzling to him; modern technology like the computer, to say nothing of the internet, is altogether incomprehensible; and when he finds out that his mother has already passed away, five years prior, the pain is too much to bear. And in the interim, while he recovers, reconnecting with his friends and colleagues proves awkward and stifling, further exacerbating the swell of alienation and loneliness he’s already undergoing.

So what of Anna? In these exchanges Krauss deploys the language of restrained expectance. Anna is torn – wanting to, on the one hand, sooth and finesse, slowly, the lost memories to the surface, or, alternatively, shake, cajole and pull from Samson the experiences they shared together, experiences that are as much a part of his identity as hers. But Samson’s condition is irrevocable; and, inevitably, Anna and Samson drift apart. There is a culpability Samson feels, and as Anna begins to lose hope, he too loses rasion-d’etre, wandering into an ineffable anomie.

The novel follows Samson back to Nevada as he embarks on an experimental project that is touted to advance science and society, and then next to the center of his material mind where he is confronted with tough questions. Why this? What now? The journey is gut-wrenching and at times almost meaningless, but in the end it is cathartic.

I found Krauss’s prose fluid, and though initially the structure, even the narrative, seemed illegible, the second half of the novel was paced well, with the requisite amount of suspense. There were a star-lode of ideas that, in and of themselves, could buttress an entirely different novel. Ideas like the authenticity of memory, the psychology of the individual in relation to habits and memory, the cognitive structure of personalities as regards memory. (I may be repeating myself with the last clause, but oh well.)

I highly recommend the book. During the past month I’ve also read Philip Roth’s The Counterlife, which I’ll attempt to a mini-review of, and on the recommendation of my mother I’ve also read Conversations with God, by Neale Donald Walsch.

No comments:

Post a Comment